I just uploaded glean-0.2.0.0 to Hackage, along with releases of the Haskell Thrift compiler and other dependencies.

Since version 0.1.0.0, Glean has been installable using plain cabal

install which vastly improves on the previous complex build

process. For full details, see Building Glean From

Source, but to summarise: on a

recent Linux distro, with GHC 9.2-9.6 and cabal 3.6+, install some

prerequisite system packages (listed in the building docs above), and

then just

cabal install glean

The build takes a while, partly because one of the dependencies is a cabal-packaged copy of the "folly" C++ library (folly-clib) and cabal doesn't currently build C++ files in parallel.

Changes in 0.2.0.0

Some pretty big things have landed:

Glean now comes with a generic LSP server, glean-lsp, which supports common IDE operations like go-to-definition, go-to-references, hover documentation, and symbol search. This means you can index a software project with Glean and then browse it using VS Code (for example). I'll give a couple of worked examples below showing step-by-step how to do this for some real world codebases.

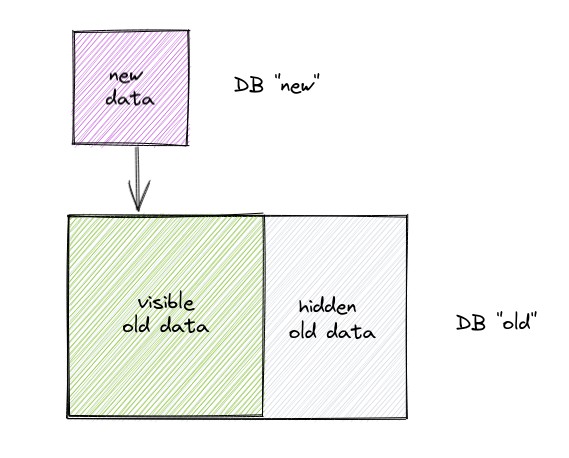

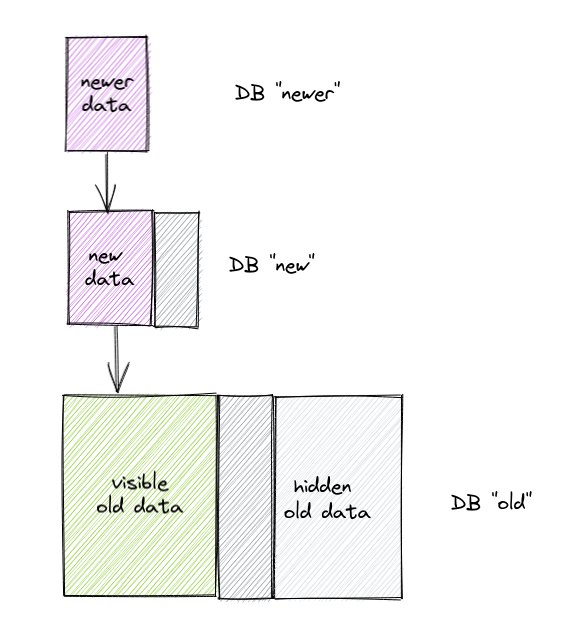

Glean has a new experimental DB backend based on LMDB. LMDB is much smaller and simpler than RocksDB, and in most of our benchmarks it performed around 30-40% better. We're still investigating some performance issues encountered with very large indexing jobs, though. Currently it's still not possible to build Glean without the RockDB dependency, but we do intend to fix this in the future.

Added a new Haskell indexer that consumes

.hiefiles directly, and collects much richer data than the old indexer - in particular it indexes local variables and collects type information for all variable occurrences, which appears on hover withglean-lspand VS Code.We're now also releasing the C++ indexer as a Cabal package along with Glean: glean-clang, so Glean can be used to index C++ projects out of the box.

Examples

Here are a couple of things you can play with, once you've built and installed Glean.

Index LLVM + Clang and browse it in VS Code

Clone an LLVM source tree:

git clone https://github.com/llvm/llvm-project.git

Configure, including Clang. This step also produces the

compile_commands.json file that Glean will later use during

indexing:

cd llvm-project/llvm

mkdir build && cd build

cmake -DCMAKE_EXPORT_COMPILE_COMMANDS=1 -DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Debug -DLLVM_ENABLE_PROJECTS=clang ..

Next, build LLVM. This step is required because LLVM includes a lot of generated code which is produced as part of the build process, so to index the source files we need to ensure all the generated code has been built first.

cmake --build . -j12

Go and get a coffee. Or two. (beware, even with 32GB this tends to OOM

my laptop, so you might want to reduce -j12 to something

lower). Next, we can index the project using Glean's C++

indexer.

If you haven't already install Glean's C++ indexer, do that:

cabal install glean-clang

Next we'll run the indexer. We'll store the resulting DB in

llvm-project/gleandb for now.

cd ..

glean --db-root gleandb index cpp-cmake --db llvm/1 --cdb-dir "$(pwd)/llvm/build" . -j12

Go and get another coffee... this is essentially running the compiler over all the C++ code again. It should need no more than 16GB or so with 12 indexer processes running in parallel.

Note that you need to do this from the llvm-project directory, this

ensures that the filenames in the Glean DB will be relative to that

directory which is what glean-lsp expects. (Storing the data under

the wrong filenames is the most common cause of things not working

when we connect up the full IDE/LSP/Glean stack).

Next we need to set up VS Code and glean-lsp. There are full

instructions for glean-lsp in its README, but here's specifically how

to set it up for LLVM using the index we just created.

First install glean-lsp if you haven't already:

cabal install glean-lsp

To use this LSP server with VS Code, you need a generic LSP client

such as Generic LSP Client

(v2). Install that extension in

VS Code, and then create llvm-project/.vscode/settings.json:

[

"glean-lsp": {

"repo": "llvm"

},

"glspc.server.command": "glean-lsp"

"glspc.server.commandArguments": ["--db-root", "gleandb"],

"glspc.server.languageId": [

"cpp", "c"

]

}

Now in VS Code, "Open Folder" and select the llvm-project folder. If

you have another C++ extension installed, it probably makes sense to

disable it for this folder, otherwise you'll see responses from both

extensions for things like go-to-definition.

Open a source file,

e.g. llvm-project/clang/include/clang/AST/Decl.h. You should have

code navigation features available: holding down Ctrl while moving the

mouse around should underline identifiers, and clicking on an

identifier should jump to its definition. You should be able to

right-click "Go to References" on a definition to find references

throughout the whole LLVM + Clang tree instantly, and Ctrl+T for

symbol search should work. Hovering the mouse over an identifier

should show its type.

If things aren't working, then the first place to look for problems is in the output window for the Generic LSP Client: show the Output window, and then select Generic LSP Client from the dropdown on the right.

You can also open the DB in Glean's shell to check that it looks right:

glean shell --db-root llvm-project/gleandb --db llvm

Try e.g. :stat to see the contents, and try src.File _ to show

known source files.

Download a DB of Stackage and try some queries

You can download a DB of Stackage

21.21

and try some queries. This DB was produced by building ~3000 packages

in Stackage 21.21 and then producing a Glean DB from the .hie files;

for more details see Indexing Hackage: Glean

vs. hiedb.

Unpack the DB:

mkdir /tmp/glean && tar xf glean-stackage-21.21.tar -C /tmp/glean

and start the Glean shell:

$ glean shell --db-root /tmp/glean

Glean Shell, built on 2025-07-14 13:39:35.711312749 UTC, from rev <unknown>

Using local DBs from rocksdb:/tmp/glean

type :help for help.

>

Load the DB:

> :db stackage/1

stackage>

Let's see what's in it:

stackage> :stat

hs.ClassDecl.3

count: 6503

size: 350074 (341.87 kiB) 0.0309%

hs.ConstrDecl.3

count: 89371

size: 4048652 (3.86 MiB) 0.3569%

hs.DataDecl.3

count: 40711

size: 2017999 (1.92 MiB) 0.1779%

...

Total: 21735709 facts (1.06 GiB)

Let's find the class declaration for Hashable. First we have to find

its name:

stackage> hs.Name { occ = { name = "Hashable" }}

{

"id": 11500325,

"key": {

"occ": { "id": 11923, "key": { "name": "Hashable", "namespace_": 3 } },

"mod": {

"id": 733072,

"key": {

"name": { "id": 733071, "key": "Language.Preprocessor.Cpphs.SymTab" },

"unit": { "id": 560159, "key": "cpphs-1.20.9.1-inplace" }

}

},

"sort": { "external": { } }

}

}

...

5 results, 20 facts, 7.40ms, 316816 bytes, 914 compiled bytes

We got 5 results, and only one of them was the one we wanted. So let's

restrict the query to find only results in the hashable package:

stackage> hs.Name { occ = { name = "Hashable" }, mod = { unit = "hashable".. }}

{

"id": 11924,

"key": {

"occ": { "id": 11923, "key": { "name": "Hashable", "namespace_": 3 } },

"mod": {

"id": 11922,

"key": {

"name": { "id": 11920, "key": "Data.Hashable.Class" },

"unit": { "id": 11921, "key": "hashable-1.4.3.0-inplace" }

}

},

"sort": { "external": { } }

}

}

1 results, 5 facts, 1.18ms, 353848 bytes, 1489 compiled bytes

OK, now let's find the class declaration:

stackage> hs.ClassDecl { name = { occ = { name = "Hashable" }, mod = { unit = "hashable".. }}}

{

"id": 19072033,

"key": {

"name": {

"id": 11924,

"key": {

"occ": { "id": 11923, "key": { "name": "Hashable", "namespace_": 3 } },

"mod": {

"id": 11922,

"key": {

"name": { "id": 11920, "key": "Data.Hashable.Class" },

"unit": { "id": 11921, "key": "hashable-1.4.3.0-inplace" }

}

},

"sort": { "external": { } }

}

},

"methods": [

{

...

}

1 results, 15 facts, 6.45ms, 514328 bytes, 1777 compiled bytes

Let's find the method names of the class:

stackage> (C.methods[..]).name.occ.name where C = hs.ClassDecl { name = { occ = { name = "Hashable" }, mod = { unit = "hashable".. }}}

{ "id": 21736733, "key": "hashWithSalt" }

{ "id": 21736734, "key": "hash" }

And finally, let's see how many instances in Stackage 21.21 provide a

definition of hashWithSalt:

stackage> :count I where B = hs.InstanceBind { name = { occ = { name = "hashWithSalt" }, mod = { unit = "hashable".. }}}; hs.InstanceBindToDecl { bind = B, decl = { inst = I }};

267 results, 267 facts, 26.40ms, 644736 bytes, 2462 compiled bytes

To see where these instance declarations are:

stackage> I.loc where B = hs.InstanceBind { name = { occ = { name = "hashWithSalt" }, mod = { unit = "hashable".. }}}; hs.InstanceBindToDecl { bind = B, decl = { inst = I }}

{

"id": 21736733,

"key": {

"file": { "id": 3982208, "key": "text-latin1-0.3.1/src/Text/Latin1.hs" },

"span": { "start": 2662, "length": 157 }

}

}

{

"id": 21736734,

"key": {

"file": { "id": 11054592, "key": "shake-0.19.7/src/General/Thread.hs" },

"span": { "start": 526, "length": 87 }

}

}

{

"id": 21736735,

"key": {

"file": { "id": 5786370, "key": "strict-tuple-0.1.5.3/src/Data/Tuple/Strict/T6.hs" },

"span": { "start": 1887, "length": 265 }

}

}

...

There are also some example queries in an earlier blog post (however, the

schemafor Haskell has changed in a few ways since that post so some of the queries might not work exactly as written).Index your own Haskell code

To index the code of a Cabal package, add the following to your cabal.project:

package *

ghc-options:

-fwrite-ide-info

-hiedir .hiefiles

Then

$ cabal build

$ glean index haskell-hie --db-root /tmp/glean --db mydb/1 .hiefiles

and then you can query the new DB in the shell:

$ glean shell --db-root /tmp/glean --db mydb/1

Run a Glass server and make some simple queries

Glass is a "symbol server", it provides a higher-level interface to

the Glean data, with operations like documentSymbols for finding all

the symbols in a file, and findReferences for finding all the

references to a symbol. I used Glass to connect VS Code to Glean in

the previous blog

post.

Glass makes requests to a Glean server, so we need to start both

glean-server and glass-server, like this:

$ glean-server --db-root /tmp/glean --port 12345

and in another terminal:

$ glass-server --service localhost:12345 --port 12346

then we can make requests using glean-democlient, for example to

list the symbols in the file src/Data/Aeson.hs in the aeson-2.1.2.1 package:

$ glass-democlient --service localhost:12346 list stackage/aeson-2.1.2.1/src/Data/Aeson.hs

stackage/hs/aeson/Data/Aeson/var/eitherDecodeFileStrict

stackage/hs/aeson/Data/Aeson/var/eitherDecodeFileStrict%27

stackage/hs/aeson/Data/Aeson/var/eitherDecodeStrict

stackage/hs/aeson/Data/Aeson/var/fp/4335/2

stackage/hs/aeson/Data/Aeson/var/eitherDecodeStrict%27

stackage/hs/aeson/Data/Aeson/tyvar/a/6101/50

stackage/hs/aeson/Data/Aeson/tyvar/a/6563/56

stackage/hs/aeson/Data/Aeson/var/encodeFile

stackage/hs/aeson/Data/Aeson/tyvar/a/7047/61

...

Each of those symbols is a "Symbol ID", which is a string that uniquely identifies a particular symbol to Glass. Using the Symbol ID we can find all the references to a symbol: